|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 CHAPTER 7 CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER 9 CHAPTER 10 |

||||||||||||||

| CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 12 CHAPTER 13 CHAPTER 14 CHAPTER 15 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER 18 CHAPTER 19 |

||||||||||||||

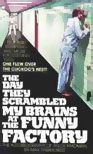

| A Novel By Max Rabinowitz | ||||||||||||||

| I was fifteen. I had just been released from the hospital on something called "convalescent care" status. This was like being on parole. You had to report to your doctor once a month and tell him everything you had done and how you felt. If at any time the doctor felt you were relapsing, he would order you back into the hospital. I was home, alone in my brother's room on the second floor of our house in Queens, when mother called up the stairway and asked me to look for our cat, who was expecting kittens at any time. I found the mangy thing after a few minutes and, sure enough, she had given birth to six tiny kittens. The mother cat was just licking them off and they were as cute as anything you ever saw. I informed my mother about the happy event, but she didn't seem very happy about it, not very happy at all. The next day she called all the children together and explained why it would be impossible to keep all of those kittens. It was mainly because of the cost of upkeep. The cost of anything was constantly on my mother's mind. My mother had already gathered the kittens into a little basket. They were all mewing for their mother, but she was locked in the basement. My mother gave me one of the tiny kittens and told me to take it to an empty lot and leave it. My sisters all protested, but my mother said the kitten was sure to be found by someone who would take care of it better than we could. This was a lie because hardly anyone entered the lot. I didn't say anything about it, but just took the tiny bundle of fur into my hand, turned and walked out of the house. As I walked the few blocks to the vacant lot I tried to avoid looking at the small bundle of fur in my hands. It was smaller than a bag of peanuts and its eyes were still shut. How would it fend for itself in an empty lot? Right then, I felt like my mother was the biggest hypocrite in the world. She knew as well as I did that the kitten had no chance for survival if left on its own. What she intended was for the kitten to starve slowly to death in that lot; out of her sight. I knew what it felt like to be abandoned and lost, without anyone, and I wasn't about to let that happen to the kitten. I just couldn't do that and still live with myself. When I entered the empty lot I searched around for a large rock. I then proceeded further into that lot and when I reached the middle I put the kitten down inside a small depression. It started mewing and whimpering as soon as I had released it from the warmth of my hand and I knew that I had best do what I had decided to do quickly, before I was rendered incapable by such a pitiful sight. I raised the large rock and slammed it down on the kitten. I only succeeded in injuring it severely. Hurriedly. I again raised the rock and this time smashed the kitten's head. It was dead. One of its eyes bulged from the socket and with a stick I pushed it back into place. It took several attempts because my hands trembled so much. I then dug a shallow grave with my hands. If that kitten was to die at least it wouldn't be of slow and painful starvation. When the hole was deep enough, I placed the kitten inside and covered it with a mixture of dirt, sticks and leaves. I took some pieces of a branch and made a crude cross to mark the grave. I had no ideas about religion, but I did want the kitten to have some type of marking. I brushed my hands off on my pants, then turned and left the lot, but I felt so bad that I didn't return home immediately. I didn't know it at that time, but I had been watched closely, from the moment I left the house. I do not know why my sister followed me but the likelihood was that she, as I, protested my mother's decision to abandon the kitten in that manner. Whatever the reasons for the surveillance, it was to prove disastrous for me, and helped to finalize the path my steps would take for years to come. When I returned home my mother was having one of her frequent fits of simulated hysteria. It was a tactic she used in order to get the sympathy, attention and obedience that she could not otherwise obtain. The minute I was in the door she started calling me "killer" and a barrage of other less pleasant names, swearing that I was crazier than a loon. Between outbursts she picked up the telephone to call the hospital authorities. I tried to explain why I had killed that kitten. My sister, in her usual fashion, had built up the incident telling my mother that I spent a long time pounding and pounding away at the kitten. I gave up trying to explain. No one ever believed me anyway. To this day, I still believe my action was the lesser of two evils. The "house of horrors" took me back and I was to spend three more years there before I made my last, and final, escape from the madhouse they had the temerity to call a hospital. Upon my return I was transferred to the adult section, probably because of the story that my mother told them and because she made such a stink over what I had done. I was sent to the roughest, most horrible building for men on the adult side of the institution. It was commonly known as K Building, but the true designation was the Violent & Criminal Center. There, within the confines of maximum security, I was to set my feet on a path that would never deviate - the path of violence and criminality. K Building was aptly named. Up until the time I entered K building I had committed many criminal acts, but mostly petty offenses like stealing small objects or piddling amounts of money. I had committed acts of violence before, though certainly not "criminal violence." Now I was to learn what violence really meant and I as to learn the true meaning of murder. In less than a year I participated in the deaths of two human beings without experiencing any sort of remorse. K Building was a filthy pesthole compared to the children's unit in Building Nine. It was three floors high and each floor had small windows firmly covered with the type of bars used in prisons and reformatories. The windows looked as if they hadn't been washed in years. The façade of the building was a dingy red brick and even in the brightest sunshine you had to look closely before you realized that the bricks were red and not a dull rusty gray. The door in the front of the building was a massive contraption, steel and wood, about seven feet high and at least three inches in thickness. The steps leading up to the building were made of solid marble, but with deep indentations in the middle where they had been worn down by the passage of countless feet. After gaining entrance through that massive door, it was locked behind me and I faced yet another door. This door was made of criss-crossed iron slats about one inch in diameter, giving it a kind of diamond design. When the outer door had been firmly secured by the first attendant the inner door was then opened. I stepped through into, a very short and very narrow corridor. On this corridor were four rooms. Two of them were doctors' offices and one of them housed the supervisory nurse's office. The last was a bathroom containing one bowl and a sink. It was a little bit larger than a broom closet. I was taken into the first door on my left, which was the office of a Dr. Trotano. I was ordered into a seat and told that the doctor would be in to see me shortly. The attendants had not yet taken off a constricting straight jacket that I had been wearing and my nose itched something fierce. It was a standard rule that anyone transferred to or from the Violent & Criminal Center had to be encased within one of those things. There were two basic types of straight jackets. The one I wore was constructed out of heavy-duty canvas, with a series of metal eyelets running up the back of it. The arms were sewed shut and from each arm dangled a long piece of rope. The idea was to place a patient into this device so that the rows of metal eyelets ran down the center of his back. Then his arms were crossed in front of him and the dangling ropes were pulled through those eyelets and laced just as someone would tie a shoe. If an attendant felt particularly good he would tie the remainder of the rope around the victim's throat where the slightest move would cause the rope to bite into the neck. Yet, these canvas straight jackets were sometimes ripped right off by enraged patients or sometimes removed by wise guys who knew the trick of getting out. I was one of those wise guys and could remove a canvas straight jacket in less than two minutes. In order to combat this the hospital had a specially designed straight jacket made out of rubberized canvas. When one was wrapped in that he didn't even try to get out because there simply wasn't any way to do it. The arms were eight feet long and the sleeves would wrap around a human about four times. At the end of each sleeve was a small leather strap and these were buckled in at the back. Since the jacket was rubberized, no one could rip his way out of it, as the really enraged patients were to do, nor could one of us wise guys slip out. The slightest exertion whatsoever caused one to seat terribly and get all itchy, sometimes even dehydrated if left in long enough. The rubberized straight jackets were the very best, but they were more expensive and were used much less than the canvas ones. As I said, my nose was itching fiercely while I waited for the doctor to put in an appearance. I couldn't scratch it because of the straight jacket and the only logical thing to do was to take the straight jacket off. I wriggled and squirmed a bit, using the technique that I had learned and after about a minute I had the thing in my lap. I was joyously scratching my nose when the doctor entered the office. The sight of me sitting there with my straight jacket off threw him into a real panic and he yelled for the attendant. The attendant, whom I later found out was Mr. Levine, barreled into the office. Without a word, he punched me in the face and I flew into the wall as if I had been shot out of a cannon. I was still stunned when he had replaced the straight jacket, tying the ends of the rope around my neck. After he plopped me back into the chair I looked right at Doctor Trotano, who had witnessed the whole thing. The learned doctor paid not the slightest attention to my look and without a word he took his seat behind the desk. Mr. Levine went into the corridor. Dr. Trotano was a big, swarthy man. He had but one large eyebrow that transverses his face from one temple to the other. I could see quite a few pits and craters in his face and also a large mole just below his right eye. He wore a loudly checked sports coat and a pair of gray pants. This outfit was practically a uniform for him and not once did I ever see any other clothing on him. He started off by telling me that I was now in the Violent & Criminal Center and that any violation of the rules would mean instant punishment. He didn't say exactly what that punishment consisted of, but I had a few ideas. Dr. Trotano went on to say that I had been sent there because Dr. Masti in the children's building felt I was of a violent bent and also thought I might be disruptive to the programming in Building Nine. I wondered what programming he meant. And I couldn't imagine anything more violent than what I had already experienced. However, I was soon to learn the difference between violent children and violent adults. He told me that I was to be lodged on Ward Seven until space could be made for me on Ward Five, which was the adolescent ward. I had heard some stories about ward five and it was a known fact that the men there were really crazy. I told Doctor Trotano that I wasn't that violent and that I didn't think I belonged in K Building. He paid absolutely no attention to anything I said. I watched him closely as we sat there. He constantly doodled on a small scratch pad with a silver-colored ballpoint pen. I wondered what he was writing, but I couldn't see it due to the angle of my seat. Just before he concluded the interview he turned the pad around so I could see what he had written. The paper was covered with dozens of insects of all kinds. "Do you see that?" he asked. When I nodded he said, "That just goes to show that you're buggy, buggy, BUGGY!!!" I wasn't sure that I was "buggy," but right then I was positive that he was! A few years later Dr. Trotano was committed to a city psychiatric hospital and after flaking out there he was sent to another state hospital further out on Long Island. Obviously there were others who felt as I did about Dr. Trotano. The attendant, Mr. Levine, pushed me onto a rickety old elevator. He took me to the second floor and then into Ward Seven. Each ward had approximately sixty patients; Mr. Levine took off the straightjacket and brought me to the attendants' office, which was located toward the front of the ward. There he introduced me to another attendant by the name of Schultz. When Schultz stood up I gasped. He must have been at least six-foot six. During a conversation a few weeks later I was informed that one of the requirements for working as an attendant in K Building was that the applicant had to be at least six feet tall, and proficient in some form of hand-to-hand combat. There were judo experts, karate experts, aikido experts and just plain "beat-the-shit-out-of-him" experts. Another thing that the attendants had in common was a streak of sadism. Because the salary was only about sixty dollars a week take home pay, only those that couldn't get employment elsewhere would apply for a job. The salary didn't draw the cream of American society and their frustration was taken out on us. The public never inspected the building and even if they had they'd only see what the attendants wanted them to see. Many times I have seen a patient beaten into a bloody pulp and, if his relatives should happen to visit, they would be told that he'd had an episode and wasn't permitted visitors until he'd calmed down. If the relatives insisted upon seeing him, and questioned the cuts and bruises, they were told that other patients had beaten him up or that he'd fallen down some stairs. Another well-used line implied that the marks were self-inflicted. My mother came one day and asked me how my eyes got blackened. I told her that an attendant smashed me in the face for not eating a slice of bread in the mess hall. She'd already been told that another patient hit me because I tried to steal his food. There was no question whom she believed. There were also two female nurses in this building and both ranked among the ugliest persons I had ever seen anywhere. They were stationed from eight a.m. to four p.m., on wards ten and eleven. These wards housed the incurably violent and had the most vicious bunch of attendants I've ever encountered in my life. The men who ran these two wards were more violent than the craziest patients, but then they had to be. In spite of their size and skill, many of them were killed by enraged patients. I never kept records but I can recall several incidents where an attendant lost his life, and there must have been more. I never even thought of counting the patients who were murdered because there were just too many. Wards Seven and Eight housed a certain type of crazy guy known as a catatonic. There were about one hundred and ten guys on both wards and at least a hundred of these were catatonics. They were all ages from sixteen to sixty. Most catatonics didn't live to be much older than thirty or so and I figured that the older ones had turned catatonic recently. There's only one way that I can describe a catatonic and it certainly isn't a scientific description. A catatonic is a guy whose brain isn't connected to his body. He's alive, but he won't move unless you move him, and any position you place him in will be the position he assumes until his death, unless he's moved again. He will not eat unless fed. He will defecate and urinate right where he is and all over himself just like a helpless little baby or something. Those guys really were in sad shape and perhaps they were better off when they did die because they certainly didn't enjoy much while they were alive. On these wards were about ten guys like myself, young, physically fit, not so crazy at all. We were kept there for the purpose of cleaning. We had to mop and scrub four times a day in order to clean up after the catatonics. There was always a pile of shit or a puddle of piss on the floor. We did the best we could, but still the place stunk like a stopped-up outhouse. The catatonics also had to be fed and each of us was responsible for ten or twelve of them. I would just shovel the food into their mouths as fast as I could, then it was on to the next man, and the next, until all of my charges had been fed. It was a difficult and messy process and one that I didn't relish in the least. I felt sorry for those guys and wished I could invent a pill that would bring them back to life. It never happened and they froze there until they eventually died. We also had to give them showers. We would strip them down and then shove about six human beings into a shower stall that was designed for only two. Then we would turn on the water as hot as we could stand it. The catatonics would just stand under the streaming water without moving or blinking as the scalding water ran right over them. Two of us would then strip down and get into that shower stall with them. We would take a scrub brush and soap them all over and then scrub them as if we were scrubbing a wall made of stone. Many of them bled because of the stiff bristles on those brushes, but there was no other method fast enough, so we were stuck with it. The few guys with sense didn't have much time for amusement on that ward. Most of the day we were either cleaning the wards or cleaning the catatonics. It was a real drag, but we made our own amusements. Sometimes we'd take two of those catatonics and set them up, like statues, in some of the most obscene poses we could think of. They would stay in any position we placed them in, so we'd put the face of one right underneath the crotch of another and then sit around waiting for the catatonic who was standing to take a piss. We thought it was really funny to see that, but in retrospect it wasn't funny at all. Once we balanced five of them as if they were building blocks, one right on top of the other. It was very strange-looking to see five guys balanced like acrobats and not one of them knew they were off the ground. They stayed that way for almost an hour, but then we had to take them apart for lunch. This we accomplished by simply pushing the bottom man and causing them all to fall into a tangled heap. Only one was slightly hurt, but even he didn't know that, so why should we care? No one else cared about them. There were also ways to make money with the catatonics. If it was a Wednesday or a Sunday there would be a one hour visit for anyone who came to see one of these men. I never could understand why anyone would want to visit a catatonic because he never even knew anyone was there, and talking to him was like talking to a wall. Not even that! At least from a wall you would get an echo, from a catatonic you got nothing but silence. Anyhow, we would take all the men and shove them onto Ward Eight and then spend the entire morning cleaning Ward Seven with disinfectant. We'd wash down the walls and ceiling, mop and wax the floors and polish the furniture. Visitors who arrived would see a shiny-clean ward and figure it was always that way. They never got to see the crowds of filthy men and sore-filled catatonics because we would take a bar of soap and fog over the window in the door of Ward Eight. When all the cleaning was done we would take turns in the visiting room with our ten patients. If one of the men we were assigned to was to get himself a visit there was a special routine. First, the attendant would open the door and yell out the name of the guy about to get a visit. If it were one of mine I would throw him off quickly, though much more gently than usual so that he wouldn't be bleeding when I brought him out. Next I would towel him dry, which wasn't done on regular shower days, and put him into a clean pair of pajamas and slippers. Then I'd take him to where his visitors were seated and sit him in a chair. That's where that money came in. I'd present him to his family or friends and tell them how nicely I had been taking care of him. They usually gave us a buck or two. In this way we could get together enough money for cigarettes and candy or whatever else we might need. There were even times when a dumb visitor would leave a carton or two of cigarettes for one of these people. On those occasions we would split the cigarettes up among all of us because the catatonics couldn't smoke and, besides, it was dangerous to put a cigarette in their mouths. The damned thing would just keep burning until it burned a hole in their lips. Neither did it make sense to give all those good cigarettes back as there was always a shortage inside. Sometimes an attendant would demand a portion of the money or cigarettes we made in this manner, but usually they didn't bother. The visiting room on any ward is a sad sight, but Ward Seven was pathetic. You'd see this man in a two-hundred-dollar suit, sitting next to another man dressed only in pajamas, holding his hand and speaking directly into his face, as if trying to make some type of contact. Those visitors acted as if they didn't know that catatonics are incapable of response. They'd ask questions like, "How are you?" and "Do they treat you good here?" and sometimes they'd even nod as if they had received an answer. I've seen many visitors in tears because they could not communicate with their catatonic loved ones. Maybe somewhere within their minds those catatonics are happy and having a good time. Maybe they enjoy mental raptures that we perceive. Or maybe they suffer the pangs of a hell that is totally incomprehensible to us. Whatever it is that goes on in their minds, if indeed anything does go there, no one has ever been able to find out. They just exist, live and die in total silence. There was one young guy in my charge that I felt particularly sorry for. He was real good-looking and he didn't seem to have anything wrong with him at all. If you just saw him sitting on a chair or standing around against a wall you wouldn't ever be able to tell that anything was wrong with him. It was only when you got close that you saw the typical blank-eyed stare that marked him as a catatonic. It wasn't the kind of look you'd see in a blind person because it was combined with a total lack of body movement. There was no twitching and not even his chest rose and fell with the breaths he must have been taking. This particular guy died one day. I don't know why or what from. We didn't find out about it until we went to move him into the shower room. I often wondered why they let men in that condition live, why they just didn't kill them off and bury them some place. It couldn't have been more inhumane than what they were doing. At times the doctors would try various kinds of treatment to bring them out of it, like electroshock therapy, but nothing that I ever saw worked. I was told that a catatonic was totally incurable and the only reasons they were kept alive was because there was hope some day of a cure. It seemed to me that they would be better off dead. |

||||||||||||||